‘Strike while the iron is hot’, the blacksmith implores. Such is the potency of this ancient advice that its wick burns brightly still, even as the fire of the industry that forged it sadly flicker and fade.

Reading that sentence back to myself, it seems to come from one who practices said advice, reaping the benefits thereof, but I can’t honestly make that claim. Like so many others who are raised in this pampered part of the world, I procrastinate until I’ve forgotten what I even intended to do in the first place. For so many years ideas have come and gone; trawlers passing into and out of my mind’s harbor like Grimsby docks in the 60s.

…and yet there I sat on the dockside, passively watching their passing, never boarding any of them.

One such ship of a notion was an idea that struck me a couple of years ago and sprang from an encounter I had with one of the stalwart street dwellers of Leeds city center, a fellow named Lee.

I began the following piece of writing on 22nd July 2018. Today – the time of writing this introduction – is 17th July 2020, which means I left it on the shelf for five days short of two years. I offer no excuses, as none there are to offer. My only hope is that in hearing this tale within a tale, you will a) judge me fairly and b) avoid making the same mistake, dear friends.

Returning to an article after such a long hiatus cannot occur without a huge dollop of hindsight – part of which was the catalyst for my returning to it now – and I have attempted to highlight this by italicising these sections of text.

—————————–

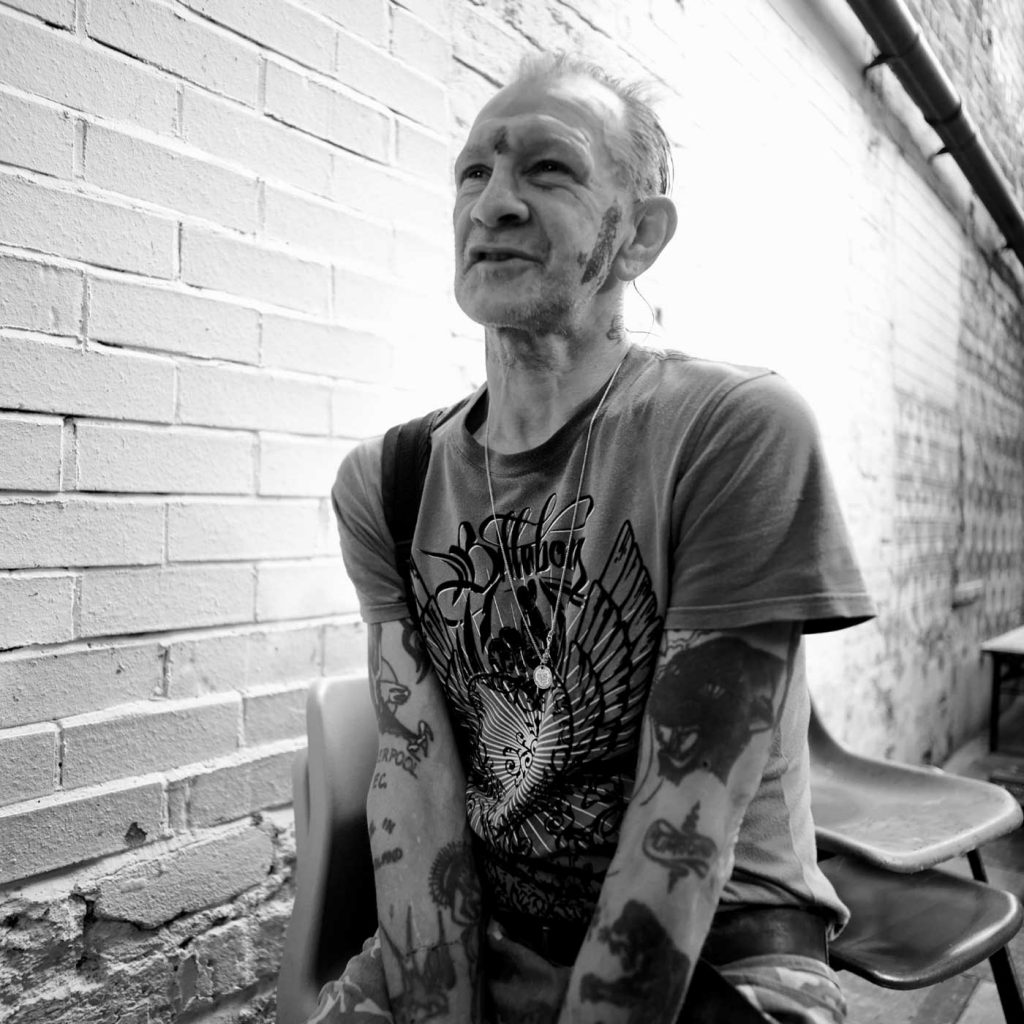

Working in city bars, I’d grown accustomed to seeing Lee almost daily as he did the rounds, searching cig bins for reasonable sized tabs, and requesting donations from smokers, his soft, almost childlike voice and West Country accent disarming many.

One of a smoker’s little joys is meeting strangers in smoking areas; hell, I’ll probably quit the shit the day I stop meeting people like Lee. Our brief conversations and exchanges of pleasantries always left my spirit a little lifted, as it does when you interact with any warm and good-natured soul.

On a nondescript day in May, Lee came by and informed me he’d had his rucksack stolen.

Knowing it was unlikely that he would find his belongings, I felt compelled to offer a little help anyway; such impotent displays of empathy as so often come from the housed and healthy.

“What does it look like, Lee? What does it have in it?”

The answer: As well as everything he owned in the world, a picture of his estranged daughter was included in the list of missing items.

“And it has a label with my name on it”, Lee told me.

“Lance Corporal Lee Harper”, he said, automatically shifting into the clipped and formal tone of a career soldier. “That’s me”, he said with pride before ambling up the street.

“Fuck, you’re a soldier”, I said aloud to myself.

It was then that I decided to interview Lee when the time was right, which of course caused ears to prick up in whichever office of global affairs enforces Sod’s Law, as having seen him daily for months, Lee suddenly became a ghost.

Last Friday, I’m sat with Chak in the beer garden at Wharf. A thin and familiar tattooed figure works his way through the tables, respectfully requesting donations from smokers.

“Now then, Lee. I was hoping I’d run into you…”

I met Chak the year before, having drifted into North Bar on my way home from work one dreary December evening. A Macanese photographer of no small repute in his home city, he’d recently moved into the Airbnb above North, with a view to scoping out the city and finding a suitable house in which to settle with his wife and son. Over the ensuing months we became very close and hung out most days. He wanted to escape Asia, to escape the workload, the din and smog of Macau, the seemingly endless attempts at imitation of his style by lesser lensmen… Mostly though, he wanted peace and time; peace to allow some semblance of calm into his incredibly active mind, and time to pursue only the kind of artistic photography that interested him. No more commercial stuff, no more big names.

One final and rather specific reason for his swiftly exiting the east was the passing of a law by Macau’s Chinese government stating that all photography in public spaces now requires official license, with penalties ranging from fines to confiscation of equipment. To a man who so highly prized the capture of an entirely natural, unaffected moment, this was high treason against the crown of free artistic expression; he had to leave. It was on hearing this that I knew I loved him as a brother.

Relocation would be to one of three cities: London, Manchester, or Leeds. Having lived in London before, he knew the trappings of the Big Smog all too well. “They’re all fucking crazy, man! Crazy! Always busy busy busy!”, he told me, adding the news that his cousin who lived there had found a knife in his son’s school bag, which he’d only started carrying because his bullies carried them also. Chak could not send his son to schools like this.

Manchester he liked, but felt it had an aggressive streak that would threaten the safety and happiness of his family. Leeds stood out to him from these three. It wasn’t too heavily developed, the people were generally welcoming, the streets felt safe, and – in his words – “It’s so fucking clean, man!” (Chak swore a lot, but somehow the cuss words never lost their meaning, in that way things tend to when overused)

In decamping from eastern hemisphere to west, ours was the city he chose.

My encounter with Lee had got me thinking how many other homeless people there are in Leeds and how readily we refer to them as “the homeless”, as though like ants or plankton they exist only as one mass. As a person of no particular note, all I have at my disposal are my words and this website. I decided to run a series of short interviews with homeless people; five questions and one photograph, aimed at highlighting the salient yet oft overlooked fact that these are human beings with lives and histories.

I’d barely even begun to explain my plan to Chak when he pledged full allegiance to the idea, offering to lend time and talent to the task. Although the plan was to keep interviews short and simple, we decided to kickstart proceedings with a more in-depth interview with Lee Harper, the forgotten soldier who inspired the project in the first place.

Keeping in contact with a homeless person can be a tricky affair, and one that in this instance took two full months of waiting for Lee to reappear. Why we did not use this time to begin interviewing others, I don’t know. We were both keen to get the project moving, so perhaps it was one of those things you plan to do in a certain order and then don’t even consider reconsidering when Plan A doesn’t pan out as expected. Instead, we waited…

Sat in Wharf Chambers beer garden on that sunny day, the two patient fishermen finally got the bite they’d been looking for, as a familiar tattooed figure came sauntering around the corner. Untrained and inexperienced, I said to Chak that this was our opportunity to make a proper arrangement with Lee to conduct the interview. Chak knew well the blacksmith’s saying and decided we should strike there and then. Ever prepared to document life as and when it unfolded, he not only had two cameras on his person, but also a decent quality voice recorder. Swiftly, he shifted a few chairs from shot and placed the recorder down before me, as I explained our intention to Lee.

Overjoyed at our desire to interview him, Lee seemed suddenly flooded with light; just as the sole passenger of a life raft afloat countless days on a darkened sea would feel his spirit return with the unexpected beam of a nearby lighthouse. Before Chak could turn the last remaining stack of three chairs into one chair on which our interviewee could sit, Lee sat himself down atop the totem, obliviously coming to rest in a considerable puddle of rainwater. Chak and I glanced at each other, but seeing no objection from Lee, came to silent agreement to follow his lead and begin the interview.

If you’ve never attempted to transcribe an informal chat or interview from an audio recording, first consider that most people don’t speak in the way that a writer writes. Hell, I’m the writer here and I definitely don’t speak this way during day to day conversation. Indeed, I have huge admiration for such orators as can be equally as erudite verbally as they are on paper; step forward Messrs Sagan, Fisk and Hitchens (no, not that one, the other one).

Add to this the blurring qualities of regional vernacular, unusual turns of phrase, conversational tangents, pauses for thought, changes of mind – and in Lee’s case the slurring of words due to medication – and a half hour interview soon becomes a full afternoon endlessly rewinding the same five seconds of audio just to make sure he said ‘out in Aden’ and not ‘Whitehaven’ (big difference).

All of this set to the soundtrack of that relentless camera shutter whose noise gave Chak his onomatopoeic nickname.

He seemed enraptured by the freedom with which he could set about his favourite business, and once confessed to me his love for the small prejudice (his phrasing, not mine) so many of us (westerners) displayed in presuming him to be ‘just another snap-happy Chinese tourist’. It was the very anonymity he’d yearned for during his last difficult years in a city he saw as too cut-throat and commercial for his art to truly flourish. Here in Leeds he was just another guy, and he relished that.

Me – So what’s your backstory, Lee?

Lee Harper – Well, I was born and bred in the West Country, more or less on the outskirts of Weston-super-mare. Mother decided – when I was about five years old – and father decided to invest around £3000 into a guesthouse, a lot of money back then. 18 bedrooms it was! D’ya know how much they got it for? £4500! A lot of money; £50,000 in today’s money, that’s what mum and dad told me.

(Here is one of those moments where unnecessary English politeness – that irritating soul-weevil that burrows beneath the skin, preventing our tree of knowledge from baring honest fruit – got in the way of me clarifying when exactly Lee was given this information by his parents. Having never been interested in fiscal affairs, I couldn’t even hazard a guess.)

LH – I was brought up in Bournemouth. Mother was doing tattooing from a young age – she started tattooing at the age of 17 – and in then she pulled out of the business… shut the busines down in her 20th year – 21st actually, it was her 21st birthday – and then they bought the guesthouse.

My father came out of the as a Sargent Major – he was based out in Aden, he was fighting in Aden. ‘course he brought himself out of the army – done twelve and a half years.

I’ve got two sisters – Kim, she’s got her own business in Torquay; she’s got two lovely boys, I’m an uncle to them. Luke (presumably one of Kim’s sons) he’s a cage fighter and for his day job he’s firefighter ‘round Devon and Cornwall. The other one plays for Torquay United – bless him – and he’s only 19. He’s played two seasons, this is his third season, and whether he’s gonna be nominated to become a pro, we do not know. But he’s been scouted by Middlesbrough, Exeter City, Plymouth Argyle and – funny enough – AFC Bournemouth! At the moment, he’s doing part-time carpentry, an apprenticeship, and doing very well.

(Having presumed Lee to have no support network, it did surprise me to hear him proudly reel off this shortlist of family members and their respective achievements. Thinking about it now, it’s silly of us to think everyone on the streets is somehow the sole surviving member of their lineage, or even that they’ve done something so terrible as to cause their family to reject them completely. I’m sure there are cases where either or both of those are true, but making sweeping assumptions about any given demographic is dead wrong.

I’ve since spent several hours hacking through the digital undergrowth to find supporting evidence for the information thus far provided; the business he said he owned, his father’s military record – Lee gave me the full names of both his mother and father, which I have omitted from this article for reasons of privacy – his firefighting nephew (I found an MMA gym in Torquay, but no Luke), as well as searching Torquay Utd’s website for the name Harper.

Several soldiers with the name Lee Harper are listed on the Forces War Records website, along with one Sgt Major who matches the full name of Lee’s father, albeit listed as being in the RAF and not the Army. I’ve sent an email requesting further information.

All else I found was one Luke Collens listed with minimal detail on the Sherdog MMA website. Your common or garden newspaper journalist would likely have made efforts to contact the fighter and eliminate him from further investigation. My weevil of politeness prevented me from doing so; ‘If he is Lee’s nephew’, asked the beetle, ‘does that mean he wishes to hear of his uncle’s plight?’

The sleeping dog of estranged families is not one to be awakened by a stranger.

Not wishing to descend further into Lee’s genealogy, I awaited a pause suitably lengthy for me to politely interject…)

Me – Tell me a bit more about yourself, Lee

LH – I left school aged 15 and a half; I went to a boy’s grammar; it was a boarding school. I left six months early to go on a Duke of Edinburgh course. I got full diplomas in artwork, craftworks, tattooing, so I went into tattooing fulltime and eventually opened a tattoo shop in Bournemouth; Ink Spot South West was [the name] I used to trade under.

I remember it was a thousand-pound lease; that wasn’t a 99-year lease, it was a 21-year lease. It was a lot of money, back then in the 70s. Something pulled me from tattooing, I’d had enough of it. I hung me guns up – I’ve still got em now – I just thought, no I’ve got to go in the army, so I entered as an Infantry PTE. My number was then 25036419; I was a PTE – Private. I work my way up and in my fourth year became a physical training instructor. Then I got a diploma in my eighth year, then wanted to become a lancer, so I became Lance Corporal in my ninth year.

Via that, I end up getting shot; after nine years. It was four and a half months into my ninth year, I end up getting shot in the clavicle, in the spine. I had twelve and a half hours of surgery.

(Here again Lee smoothly switched to military speak as he rattled off his service number, and almost saluting after his flattened palm pointed to spot where the bullets had entered. I do feel quite capable of looking a person in the eye and knowing when they’re telling the truth – or at least when they think they’re telling the truth – and the effortless way in which Lee recounted his story to me did not smack of contrivance.)

Me – Where were you serving then?

LH – Well, I went to Northern Ireland, I’d been to Germany – loved that, 19 churches on this island in Germany! – then Cyprus, Malta… my last duty was Bosnia side of Croatia; at the border. The Croatians were coming over, sniping themselves [their own people] in Bosnia, and shooting pregnant mothers. Terrible; it was not very nice at all.

So I had to pull out of the army, which was disappointing, because I wanted to do my twelve years so I would get my full pension. I didn’t even get that. I get nine years pension and I every five weeks they pay that; I don’t get benefits because of that and I’m trying to fight my case at the moment; I’m entitled to it cuz I paid my National Insurance while I was in the army, and all the various other things you pay.

I became homeless when my wife had stomach cancer two years ago; the house was in danger of being repossessed. I go to church every Wednesday and Sunday, and I pray.

I could say a lot more…

I still keep in touch with friends who were in the armed forces – in my regiment – they write to me and I write to them.

(Here again I find myself wishing I had questioned further. How does Lee keep an open line of written communication with his former comrades in arms? He says the army has washed their hands of him, so surely they don’t still handle his mail. Can a homeless person have a PO Box address? Google said ‘not really’, but gave me some other interesting results, which I shall discuss later.

Mention of his wife’s illness and the subsequent risk to their family home was swift and fleeting; was this from shame, from sadness, or was something being hidden?

I felt – or would like to believe I felt – that Lee brushed passed these events because it was simply too painfull. “I could say a lot more”, he said. Should I have pressured him to do so, in that way our reporters and interviewers do on the television?

‘Mr Minister! Mr Minister! Answer the question!’ No, I should not have done this.

My original reason for starting this project wasn’t to trip up a vulnerable individual, it was to allow him some small platform from which he could tell his story, and that’s what he did.

Feeling more like Pacman than Paxman, I shall not position myself as the grand inquisitor, interrogating my captives with torch and torture. No, I shall allow them to feed me the dots, and shall happily gobble up each one so as to place them before what readers I may have; allowing you to connect them, dear friends.

Lee’s phlegmatic exit was somewhat prolonged by Chak who, not shy of the tattooist’s gun, wanted to get some clearer shots of our homeless friend’s decorated dermis. Lee pointed out a face on his inner left bicep, claiming to have carried out the work himself.)

LH – I love tattooing. When I go in the hostel – £15.50 a night, so it’s not every night I go in there, as I don’t raise that every night – and I watch that program on tattooing, comes on early hours of the morning [he meant the show Tattoo Fixers, with all three of us agreeing that it primarily showcased terrible tattooists demonstrating incredibly poor practice].

I’m gonna shoot now, but did you enjoy that?

(Yes, I had)

Time passed by, dragging life along with it like a busy parent with a petulant child. Two decades or more of professional photography behind him, as well as some in-depth documentary projects, Chak of course got the edited photos over to me within a few days, along with the recording of my chat with Lee Harper.

Having since found and purchased a permanent home, Chak had sent for his wife and son – both of whom I also came to love, and whose names I shall not include here, likewise Chak’s birthname.

His wife’s default setting was one of nonchalance, with probably the best resting bitch face I ever saw, such countenance as made perfect counterpoint to Chak’s constant wisecracks and impassioned rants. In between rolling her eyes in the most perfect of ways, she would occasionally burst out of her stoic shell with short explosions of laughter, dispelling the notion that she was in any way mean-spirited or overly serious.

Their son was entirely a child of the future, endlessly making bonkers videos with hilarious and ridiculous special effects, from as young as three, Chak told me. Caring not a jot how formal or otherwise any given location may be, he would dance about, competitively exchange facial contortions and weird noises with me and his father, and in doing all of this gave me warm reminder of my own nephews and nieces.

Though not wishing to take on too much commercial work, Chak of course needed to fund life in England, which of course meant he and I had less time to hang out, less time to work on our ideas. That said, the reason we never got further with our homelessness project was the same reason why this very article has sat on my computer for two years:

I did not act.

Some months later Chak invited me to dine with him and his family at a pizza place in the city center; he had to tell me something. His wife, his son and I ordered pasta dishes. Chak opted simply for soup. The atmosphere was heavy and conversation seemed stuck at exchanges of social pleasantry, none of which was ordinary for any of our number.

“What is it, Chak?”, I eventually asked.

Sat next to me, he looked into my eyes with an expression of finality.

“Fucking cancer, man”

He indicated to his stomach and collarbone in the same way Lee Harper had done when showing me his bullet wounds all those months ago in Wharf Chambers. His wife turned her head from her son who was busy abusing Chak’s phone.

Serious silence clanged.

Waitress enters stage right, our steaming food in hand. As genuinely affable and cheery as most of this city’s hospitality workers, she soon noticed she’d walked right into a moment, and did wonderfully well to swiftly alter her manner from informally chirpy to respectfully neutral. I could tell Chak appreciated this, as did I, and it gave me another reason among many to champion this city’s hospitality industry.

Chak was of the same opinion as me about this hardworking army who work long hours on low wages to provide the rest of our city’s workforce much needed respite and recuperation, as well as places to meet old friends, make new ones, and simply share space with strangers. Chak and I knew how vital that last point really is, and it was in these places that my brief but lifechanging friendship with him began and ended, so thank you to those workers from the depths of my soul.

Chak loved our city. He loved our bars and the people who worked in them. He loved our grassroots movements, our charities, and our collectives. Like me, he loved that our football team wasn’t top-flight, because he understood that cities with top-flight teams can often become swamped solely by the culture of that sport, leaving precious little room for other aspects of human culture, in particular our subcultures. He loved our eclectic architecture and the way everyone seemed to love Leeds but nobody seemed to be from here. He deeply loved and respected our electronic music scene, seeing it as something like the tight knit punk scenes he’d witnessed as a youth; this was another parallel he and I shared.

Some time after our meal together, he flew to Taiwan for treatment, returning to England a month or so later. I saw him once or twice more before all contact abruptly ended, and most of his online presence disappeared. I struggled with this until very recently, wondering if I’d upset him in some way. Ultimately, I concluded that he didn’t want me to see him deteriorate. I know he will have thought deeply about what memory of him it would be best for me to retain; he had pride and I respect that from a man who taught me much in a very short time.

Even now, I still learn from him. His latest lesson: just fucking do it, man. Do it and do it now if it means a damn to you. Because if you do not, life may come along and shut that window for good.

As for Lee Harper, his presence in the city also became gradually scarcer, that same parasitic organism consuming him as I can only conclude it has done Chak. Lee’s behavior become gradually more desperate and I’ve heard from certain quarters that he’s become too erratic for some of our city’s establishments to permit him entry into their beer gardens. To date, I don’t know what’s become of him.

For my part, I owe both of these men an apology; I sat and I waited and I pondered and I mused in that way I’ve been prone to my whole life.

Lance Corporal Lee Harper; solider, father, artist, drifter, Leeds resident.

Chak; artist, father, husband, brother, lover of free expression, Leeds resident.

Every word of this article and every tear spilled during it’s writing I dedicate to you both, along with the promise to you and to myself that never again shall I allow a good idea to fall untouched by the wayside.

And you, dear friend… what will you do with your idea, your plan, your project sat on that ever-growing backburner.

Will you wait?

Or will you strike?

Words: Josefus Haze

Images: Chak